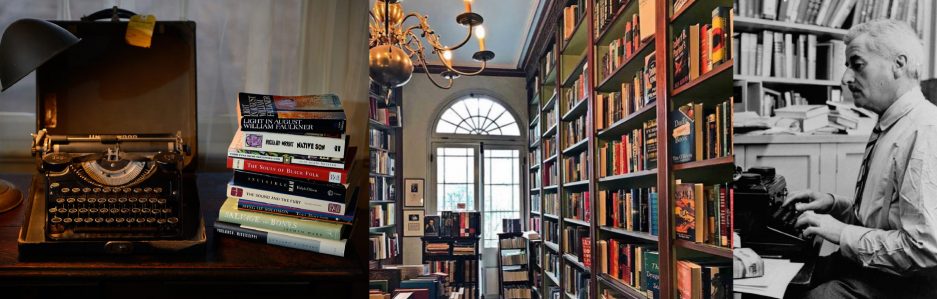

“Smoke” in Knight’s Gambit

“Barn Burning” in Selected Short Stories

Is justice achievable? Or is justice an ideal that we aspire to but find contentedness with partial completion?

Justice is one of those big, atmospheric words like love and hate, good and evil, which we use colloquially to describe otherwise normal occurrences in daily life. Our sense of justice is part of the human condition; it is cross-cultural and flows freely through language barriers. Justice is rooted in the human heart, which—as William Faulkner said in his 1949 Nobel Prize in Literature acceptance speech—is “in conflict with itself.” Only such subjects dwelling in the human heart are “worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat.”

I was already a third of the way through law school when I learned that literature could help define this ideal we call justice. Reading case law taught me to read actively, but not every judge writes with the eloquence of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., and judicial opinions are too narrow to define justice in a larger sense. Alternatively, literature is timeless, and helps us cope with problems for which there are no immediate solutions.

As a young boy, Faulkner attended courtroom proceedings and traveled around with his uncle, who was a practicing attorney. Faulkner, although not a lawyer, was a brilliant observer of the human condition and wrote about justice in many settings. Some great examples are found in a couple of Faulkner’s short story collections.

The Knight’s Gambit (Vintage, 2011) collection features six mystery stories based on Gavin Stevens, the Harvard-educated prosecuting attorney in Yoknapatawpha County. “Smoke” was the first of the six Gavin Stevens stories, originally published in Harper’s in 1932, about two brothers and a murder arising out of a land dispute. The narrator describes his uncle, Gavin Stevens, as:

“a loose-jointed man with a mop of untidy iron-gray hair, who could discuss Einstein with college professors and who spent whole afternoons among the squatting men against the walls of country stores, talking to them in their idiom.”

In “Smoke,” the young narrator reports on various opinions of justice in the community. Before Judge Dukinfield is murdered in the story, the trial audience sits for an “overlong time” while the judge validates the authenticity of “a simple enough document.” But the young narrator waits with deferential patience, as he explains:

“[Judge Dukinfield] was the one man among us who believed that justice is fifty per cent legal knowledge and fifty per cent unhaste and confidence in himself and in God…. So we watched him without impatience, knowing that what he finally did would be right, not because he did it, but because he would not permit himself or anyone else to do anything until it was right.”

The circumstances of Judge Dukinfield’s murder are what allow Gavin Stevens to see the brothers’ guilt. A skilled litigator, Stevens lures the brothers into confession while examining them on the witness stand. During questioning, the narrator emphasizes the county attorney’s thoughts on justice in a parenthetical aside:

“Ah…. But isn’t justice always unfair? Isn’t it always composed of injustice and luck and platitudes in unequal parts?”

Justice is the subject of other stories in Knight’s Gambit about Yoknapatawpha characters, townspeople and rural recluses, with Gavin Stevens leading the investigations and prosecutions. However, “Barn Burning” is perhaps one of Faulkner’s most famous short stories—first published in Harper’s in 1939 and now found in Faulkner’s Selected Short Stories (Modern Library, 2012)—that serves as a prequel to the “Snopes Trilogy” (The Hamlet; The Town; The Mansion).

“Barn Burning” is a story about justice and injustice, retribution, economic inequality, and fathers and sons. We see justice—and one’s reaction to injustice—less in the opening cheese-smelling courtroom scene, presided over by the Justice of the Peace, than we do in the actions of Abner Snopes, a sharecropper who is forced to move his family for the twelfth time in ten years. Abner is a man of “wolflike independence,” “courage,” and “ferocious conviction.” His habit is building small fires, neat and easy to control, but, in response to injustice, he shares the flame with the landowner’s barn and other property. Faulkner reveals through the thoughts of Abner’s son, Colonel Sartoris “Sarty” Snopes, that:

“the element of fire spoke to some deep mainspring of his father’s being, as the element of steel or of powder spoke to other men, as the one weapon for the preservation of integrity, else breath were not worth breathing, and hence to be regarded with respect and used with discretion.”

When the Snopes family arrives at their dilapidated tenant house, Abner goes to speak to the man who will “begin tomorrow owning me body and soul for the next eight months.” He takes Sarty with him through a grove of oaks and cedars to a fence of honeysuckles and Cherokee roses enclosing the landowner’s brick-pillared home. Inside, Abner ruins a hundred-dollar imported rug by stomping horse manure on it and, thus, becomes further indebted to the landowner. Yet again, Sarty must decide among competing senses of justice—justice under the law or justice for blood, that of his father.

“Barn Burning” was the first of Faulkner’s works that taught me to look deeper into the fictional characters’ problems for help in answering my own, for help in considering societal questions posed in the newspapers and law school courses. Knight’s Gambit was a suggestion of Joe DeSalvo, the owner of Faulkner House Books, and although I do not agree with Gavin Stevens that justice is always unfair, I appreciate his honesty. Whether in literature or in the law, we need the reminder: justice is often an unequal composition of injustice, luck, and platitudes.

-Alex B. Johnson, Faulkner House Books

I very much appreciate you discussing the short story “Smoke” by Faulkner. There’s a problem with your summary of the story, however. The brothers are innocent and it is their cousin who is discovered to be guilty of the murder.