Earlier I wrote that World War II began for me on December 4, 1941, the day before my 9th birthday, when my mother’s younger brother, who lived with us and shared a bedroom with me, was inducted into the army. Three days later, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. These two events awakened in me an unquenchable yearning to understand humanity’s greatest folly. The history of World War II became a reading obsession and the most recent book is Anthony Beevor’s Ardennes 1944: The Battle of the Bulge (2015). I had read his Stalingrad, an exhaustive, illuminating and brilliant history of a bloody and pivotal conflict, the first major setback for the Third Reich. Ardennes 1944 is equally praise-worthy. Two, albeit remote, personal connections and an awareness that three prominent American writers were combatants in the Battle also drew me to Beevor’s latest book.

The German Ardennes offensive surprised our military commanders. The war in Europe, they felt, was virtually over; victory was weeks away. Paris had been liberated and Allied forces were at the Rhine River.

Adolph Hitler, feeling invincible after surviving a botched assassination attempt, was convinced that the alliance of the United States, Britain, Canada and France was fragile and would likely fracture if seriously challenged. To that end, a major force of two Panzer armies, brought to full capacity with older men, younger boys and with units moved from the Russian front, launched a surprise attack through the Ardennes Forest on December 15, 1944. Though the counter-offensive began immediately, within two weeks German tanks and troops had advanced 90 kilometers through the middle of Allied forces, trapping several units.

The 101st Airborne Division, commanded by General Anthony McAuliffe was encircled at Bastogne, Belgium. Though weakened by recent bitter fighting in Holland, it was moved there on December 18th. Four days later a German truce delegation approached General McAuliffe’s Headquarters with an ultimatum: to surrender or face annihilation. The General’s one-word response was “nuts.” Airdrops of critical supplies enabled the Division to maintain its defense until General George Patton’s tanks broke through the enemy lines on December 29th. The next day Patton himself entered Bastogne wearing his trademark pearl-handle pistols.

Soon after the German attack began, my father received a notice to report for an army physical. He was 33, married with three children. He passed the examination and was ordered to report for training on February 1, 1945. I still recall the overwhelming gloom; the worry—how would we manage?—and the fear—mother and I were aware of the enormous casualties, many from the unrelenting frigid weather. Troop replacements were hastily trained younger boys or, like my father, older men.

Near the end of January and after suffering 80,000 casualties, what remained of the two Panzer armies had been pushed back to the German border. The Russian winter campaign had begun and my father’s army induction was canceled. In less then 4 months, Allied armies entered Berlin, Hitler killed himself and Germany surrendered unconditionally on May 8, 1945.

Ten years later, I am a 22-year-old recently commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Military Police Corps at my first duty station, Ford Hood, in Killeen, Texas. General Anthony McAuliffe is the port commander. Late on Sunday afternoon the M.P. at the Fort’s main gate stopped an erratically driven car from exiting the Fort. A few minutes of conversation convinced the M.P. that the driver, a Captain, was drunk. He then called me—I was the duty officer that day—and said I needed to come and resolve the matter since an officer was involved. Amid the storm of abuse that greeted me, he insisted that he had to return that day to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio. Much too risky, I concluded. So we locked the car, left the keys at the main gate, and I arranged for the Captain to spend the night in the Bachelor Office Quarters. His final threat was that I would regret my decision and should expect to be before the post commander in the morning.

Sure enough, waiting at Company Headquarters on Monday morning was an order for me to report immediately to General McAuliffe. The meeting was military formal. The General asked what had occurred Sunday afternoon with the Captain. I explained the Captain’s incapacity to drive safely, his behavior with the gate M.P. and with me, and the action I felt it essential to take. He listened without interruption and acknowledged that what I had done was proper. He apologized for the Captain’s attitude and explained that he obviously had too much to drink at a reunion celebration for men who had been trapped at Bastogne 10 years earlier. He thanked and dismissed me.

Not attending any reunion were the three prominent American writers who fought in the Battle of the Bulge: Ernest Hemingway, J. D. Salinger and Kurt Vonnegut.

Ernest Hemingway was a war correspondent, but journalism wasn’t a high priority. He demonstrated his fearlessness under fire many times.

J.D. Salinger, with the 12th Infantry Regiment, wrote short stories throughout the Battle whenever he could find an unoccupied foxhole. He was fortunate enough to receive a fresh pair of knitted woolen socks each week from his mother.

Kurt Vonnegut, the least fortunate of the three, was in the 423 Infantry Regiment. His fellow soldiers he described as a mixture of college kids and others who had likely enlisted to avoid jail. His regiment, encircled by German artillery, chose surrender rather than annihilation. Some 8,000 men were taken captive. It was the second largest of the War after the Bataan Death March in 1942. In his novel Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut writes about the horrors of war. He survived the firebombing of Dresden where he was held prisoner.

So there you have it: a good book, a bit of history, some literary trivia and a touch of the boy and the young lieutenant I once was. For the last I ask your indulgence. At 83, I seem to spend more time remembering than I do dreaming. My sincere desire remains, however, not only to share what I’ve learned but also to use what I know to help me learn what I don’t know. One is never too old for that.

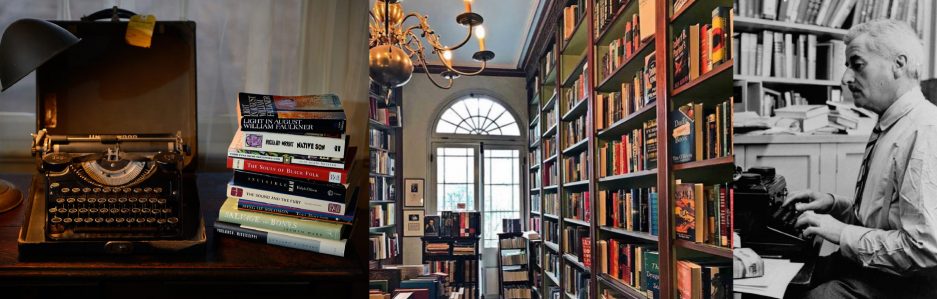

-Joe DeSalvo, owner, Faulkner House Books