Frank Stanford has long been a kind of enigma in the poetry world: an underground legend, with a cult following, whose work has always been notoriously difficult to find. Though he died in 1978, at only 29 years old, this is the first time that his collected works have been available for purchase. What About This will hopefully usher in an era when Stanford’s work is rightfully regarded as seminal American poetry for generations to come.

Stanford is a writer unlike any other American poet of his time. His work is reminiscent in its scope and dialect of Whitman, but he was also heavily influenced by French and Latin American Surrealism. This collection includes not only all of Stanford’s published work (except for the epic The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You, which is excerpted throughout the collection), but also his many unpublished manuscripts, one of which, titled Automatic Copilot, is composed entirely of poems written after the work of other artists. This manuscript is one of the great gifts of this book, as Stanford shows us the work that was most important to the creation of his own art. His poem “Cave of the Heart,” after Lorca, exemplifies that surreal, almost Romantic influence:

Drenched in the lost blood of the moon, yawning

In the furrows turned after dark, your thick legs long as feathers,

Stout as brooms, the earth you sleep on

Too young to call a grave.

Stanford was constantly in conversation with the work of other poets, while at the same time forging his own unique place in American poetics. He used local diction from his ancestral homes of Mississippi and Arkansas, illuminating a world often unseen by the majority of America. Throughout his collections Stanford writes “Blue Yodel” poems; for example, “Blue Yodel of Her Feet” in the collection You:

Your chest gives ground

Like an island on a river

And as they yodel in the song of songs

Your nipples taut as raisins

Killdeers try to fly from your eyes

I wish I could nail your shoes to the floor

And lose your socks

Stanford combines, in poems like this, the surreal, the local, the beautiful, and the mundane, building it all up to create a narrative of love that seems something out of a dream. The poem is a “yodel,” a mountain song echoing, yet it is about a woman’s feet, literally her lowliest part. Stanford does not differentiate between the high and the low; rather, he sees the poetry in everything, and reveals it to the reader through inventive language and free-flowing form.

In Constant Stranger, perhaps the strongest of his published manuscripts, Stanford writes of love and death as equally strange and familiar, the two most inevitable aspects of life, which haunt his poetics in equal measure. This collection begins with “Death and the Arkansas River,” a long poem in which death is portrayed as a sort of local legend, who is simultaneously powerful and quotidian:

Some say you can keep an eye

Out for Death,

But Death is one for fooling around.

He might turn up working odd jobs

At your favorite diner.

He might be peeling spuds.

These poems are truly, in the words of the New York Times’ Dwight Garner, “death-haunted.” It is impossible to wholly separate the work from the life of the artist, whose death at 29 of three self-inflicted gunshot wounds to the heart, as well as his precocity and style, make him comparable to a sort of American Rimbaud. In the poem “Time Forks Perpetually toward Innumerable Futures in One of Them I Am Your Enemy,” Stanford begins with the line, “I am going to die.” He goes on,

Death is an isthmus, you can get there on foot.

But love had made its island.

…

Tell it:

There is a fear without age or Christ

That goes through us

Like moonshine in a coil.

Stanford consistently takes those two most ancient poetic themes–love and death, that which is most feared and most desired–and infuses them with the freshness of his language and imagery. These poems are suffused with images of the Ozarks: the moon shining on water, boats, catfish and alligator gar, trucks and small-town bars. To read his figuration regarding the moon, in particular, is an almost transcendent experience. For example, in “Women Singing When Their Husbands Are Gone,” from Ladies From Hell:

Flies wanting a warm place to stay

And the threequarter moon

Quieter than a child slicing a melon

Like dirt smeared over with seeds

And in the titular “What About This,”

Things are dying down, the moon spills its water.

Dewhurst says he smells rain.

In these poems, the moon, like love and death, becomes more than a symbol; it is almost a character in itself. The poet constantly doubles back over and around the same themes and images, creating a kind of dreamscape of Southern mountain surreality. There is something undeniably sublime about the best of Stanford’s work. This is the kind of book to read before bed, so that his images may permeate your dreams.

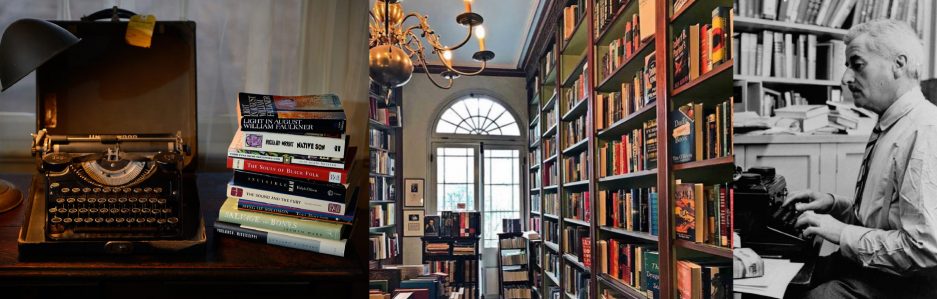

-Jade Hurter, Faulkner House Books