Helen MacDonald. H is for Hawk. Grove Press, 2014. 26.00.

All summer long a family of Mississippi Kites nested in a centuries-old Live Oak tree sprawling over shotgun houses across the corner of Octavia and Chestnut Streets. I noticed these sleek, soot-colored raptors soaring above me in the windy sky on Mother’s Day—never beating a wing—only slightly tilting their tails for direction. According to an Audubon Society field guide, adult Kites weigh about ten ounces spread across a three-foot wingspan. These silent hunters feed mostly on cicadas and flying insects, but also eat small rodents and birds.

Walking the dog this summer was much more interesting than usual because I was reading Helen MacDonald’s H Is for Hawk (Grove Press, 2014), a tripartite story about the author’s love for her recently deceased father, for birds and nature, and for literature. MacDonald is a poet, historian, naturalist, and falconer. H Is for Hawk—a New York Times bestseller and winner of the UK’s Samuel Johnson Prize and Costa Book of the Year—displays her varied talents because it is not a simply a “birder” book. Rather, its many layers are inspirational for anyone familiar with grief and loss, or anyone ready for a change in life.

MacDonald is struggling to say goodbye to her father, a photographer, who taught her to find the memorable aspects of life’s otherwise mundane moments, and to savor them.

Now that Dad was gone I was starting to see how mortality was bound up in things like that cold, arc-lit sky. How the world is full of signs and wonders that come, and go, and if you are lucky you might see them. Once, twice. Perhaps never again.

MacDonald describes the prehistoric reality that birds of prey are beautiful killers. She meets nature—in all its wildness—with her own emotions, blending the acts of training a Goshawk with the process of exorcising grief and depression:

They were things of death and difficulty: spooky, pale-eyed psychopaths that lived and killed in woodland thickets. Falcons were the raptors I loved: sharp-winged, bullet-heavy birds with dark eyes and an extraordinary ease in the air. I rejoiced in their aerial verve, their friendliness, their breathtaking stoops from a thousand feet, wind tearing through their wings with the sound of ripping canvas.

MacDonald considers her Goshawk killing to eat while illuminating her acceptance of death:

How hearts do stop. A rabbit prostrate in a pile of leaves, clutched in eight gripping talons, the hawk mantling her wings over it, tail spread, eyes burning, nape-feathers raised in a tense and feral crouch…. The borders between life and death are somewhere in the taking of their meal…. Hunting makes you animal, but the death of an animal makes you human.

Throughout the book, she parallels T.H. White’s The Goshawk—and often his Arthurian novels, adapted into Disney’s The Sword in the Stone—as a modern balance to her experience training a Goshawk. White’s abusive youth and life as a closeted gay man led him to write about desolation, hunting, and the desire for freedom. To contextualize her modern falconry stories, MacDonald offers a cultural history of falconry to show these raptors’ permanence in our world. Hawks “conjure history,” for example:

For thousands of years hawks like her have been caught and trapped and brought into people’s houses. But unlike other animals that have lived in such close proximity to man, they have never been domesticated. It’s made them a powerful symbol of wildness in myriad cultures, and a symbol, too, of things that need to be tamed…. The birds we fly today are identical to those of five thousand years ago. Civilizations rise and fall, but the hawks stay the same…. History collapses when you hold a hawk…

Her story motivated me to keep watching my Mississippi Kite neighbors soaring overhead. I would follow the Kites around the block, watching them float, turn, and dive each morning and evening until mid-September when they migrated from the neighborhood for warmer weather. MacDonald explains how learning about our environment helps us learn about ourselves:

What happened over the years of my expeditions as a child was a slow transformation of my landscape over time into what naturalists call a local patch, glowing with memory and meaning.

Since finishing H Is for Hawk, I have noticed more amazing birds in my New Orleans “local patch”: Bald Eagles, Osprey, Cooper’s Hawks, Quaker Parrots, Red-Bellied Woodpeckers, Painted Buntings, and more. The often-mundane task of walking the dog now glows with memory and meaning. I have Helen MacDonald to thank for that, and I cannot forget H Is for Hawk—I can only recommend it.

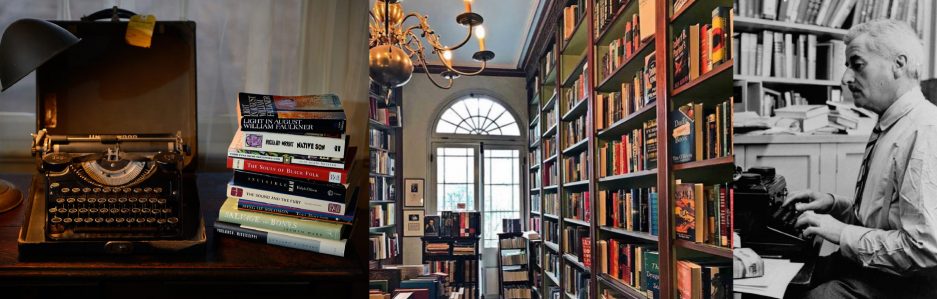

– Alex B. Johnson, Faulkner House Books