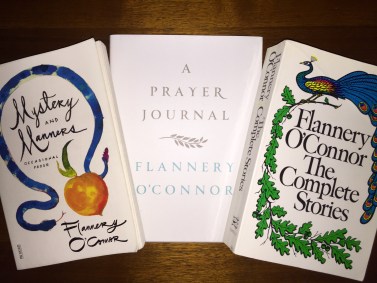

Flannery O’Connor, Prayer Journal ($18), Wise Blood ($15), Mystery & Manners ($16), and The Complete Short Stories ($18)

Futurebirds, “Sam Jones,” Hampton’s Lullaby

On Easter Sunday, this north Georgia Baptist sat in a New Orleans Catholic church thinking of Flannery O’Connor. I recently finished Mystery & Manners, O’Conner’s posthumous publication of essays and lectures about writing, religion, and peacocks. Mystery & Manners led me to several so-called “Southern gothic” short stories from The Complete Short Stories collection. So there I sat in St. Francis of Assisi’s stained glass-colored nave with a head full of Flannery O’Connor’s characters—murderers and grandmothers, a bigot barber, and a Bible salesman who ran off with a woman’s wooden leg after she seduced him, leaving her one-legged up a ladder in a barn’s second floor.

The priest’s sermon directed us to confront Easter confusion with Easter faith and, in full embrace, surrender ourselves to the mystery of life. The priest read from the Gospel of John, showing how Mary Magdalene walked in the dark before dawn and discovered that new life had risen from the tomb.

My wife and I recently read aloud O’Connor’s Prayer Journal, which she wrote when she was 21, away at college and drafting Wise Blood. It offers an intimate connection between reader and author because, in reading someone’s prayers, we recognize shared insecurities and fears. For example, O’Connor writes, “My mind is a most insecure thing, not to be depended on. It gives me scruples at one minute & leaves me lax the next.” She prays for divine strength to restrain her ego from eclipsing her view of God: “You are the slim crescent of a moon that I see and my self as the earth’s shadow that keeps me from seeing all the moon.” She prays for grace and for faith. She admits confusion and prays for Christian principles to “permeate” her writing.

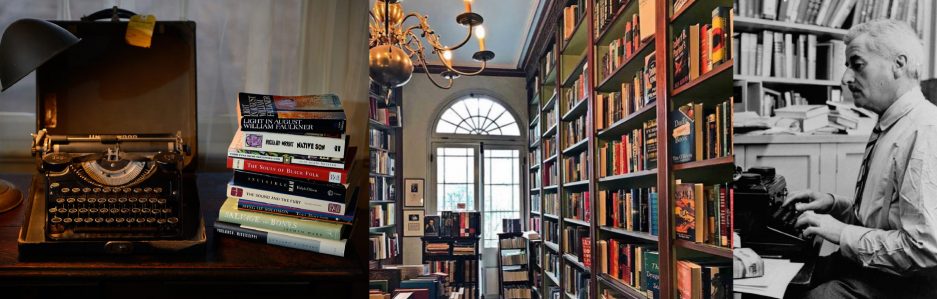

I asked Joe DeSalvo (owner of Faulkner House Books) about the Prayer Journal and he responded that, “Any writer who wants to be a great writer must read Mystery & Manners.” I quickly appreciated Joe’s advice when in the first chapter, “The King of the Birds,” I underlined and reread a dark truth: “Necessity is the mother of several other things besides invention.” Her clarity of verse draws us closer to understanding the human condition.

In her essay, “The Catholic Novelist in the Protestant South,” O’Connor discusses living with the teetotaler descendants of famous Methodist evangelist, Sam Jones. It reminded me of a song, “Sam Jones,” by Futurebirds, a critically acclaimed Athens, Georgia-based band. A full century after Sam Jones converted Tom Ryman, the riverboat casino and country music barroom owner, Futurebirds’ Sam Jones gives up on the mystery of life, scratches lottery tickets and waits to die.

O’Connor argues that Southern identity is found not at the surface of “mocking-birds and beaten biscuits [or] hookworm and bare feet,” but in the deepest “qualities that endure,” passed along generations of scripture-haunted people living in the balance of good and evil. Futurebirds’ Daniel Womack questions over a whining pedal steel guitar, “Sam Jones, are you liking what you see?” O’Connor may answer that the truth “is known only to God, but of those who look for it, none gets so close as the artist.”

O’Connor demands that artists and writers stare at everything possible to seek meaning worth extracting. She worries about her generation, which was groomed to eliminate mystery. She defends herself as a Christian writer because, having embraced the mystery of Christ’s resurrection, she is able to see other mysteries of life on earth.

During St. Francis’s Easter service, a little boy sat doodling in the pew behind us. At a quiet moment, he shouted to his mother, “I found the mystery!” In good manners, his mother shushed him.

O’Connor writes about people and their manners which, she argues, reveal to the reader—and writer—mysteries of the human condition. She claims that she did not know her Bible salesman would steal the woman’s wooden leg until five lines before he stole it. Like Mary Magdalene on the first Easter, O’Connor walks in the dark until she has discovered the story worth sharing.

Below is a sampling of her advice to writers about good writing.

–Alex B. Johnson, Faulkner House Books

On grace:

“In my stories a reader will find that the devil accomplishes a good deal of groundwork that seems to be necessary before grace is effective…. There is a moment in every great story in which the presence of grace can be felt as it waits to be accepted or rejected, even though the reader may not recognize this moment…. And frequently it is an action in which the devil has been the unwilling instrument of grace.”

On good fiction:

“A story that is any good can’t be reduced, it can only be expanded. A story is good when you continue to see more and more in it, and when it continues to escape you. In fiction two and two is always more than four.”

On mystery and manners:

“It is the business of fiction to embody mystery through manners, and mystery is a great embarrassment to the modern mind…. The mystery [Henry James] was talking about is the mystery of our position on earth, and the manners are those conventions which, in the hands of the artist, reveal that central mystery.”

On the job of a writer:

“The writer operates at a peculiar crossroads where time and place and eternity somehow meet. His problem is to find that location.”

On experience:

“If you can’t make something out of a little experience, you probably won’t be able to make it out of a lot. The writer’s business is to contemplate experience, not to be merged in it.” (84)

On perception:

“The beginning of human knowledge is through the senses, and the fiction writer begins where human perception begins.”

On drawing:

“Any discipline can help your writing: logic, mathematics, theology, and of course and particularly drawing. Anything that helps you to see, anything that makes you look. The writer should never be ashamed of staring. There is nothing that doesn’t require his attention.”

More on looking:

“But there’s a certain grain of stupidity that the writer of fiction can hardly do without, and this is the quality of having to stare, of not getting the point at once. The longer you look at one object, the more of the world you see in it; and it’s well to remember that the serious fiction writer always writes about the whole world, no matter how limited his particular scene. For him, the bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima affects life on the Oconee River, and there’s not anything he can do about it…. People without hope not only don’t write novels, but what is more the point, they don’t read them. They don’t take long looks at anything, because they lack the courage. The way to despair is to refuse to have any kind of experience, and the novel, of course, is a way to have experience.”

See also, generally, David Griffith’s Paris Review article, “Reading Flannery O’Connor in the age of Islamaphobia.”