This Thanksgiving, I gave thanks for a growing family, good friends, and The World’s Largest Man: A Memoir (HarperCollins, 2015) by Harrison Scott Key.

The World’s Largest Man is the funniest book I’ve ever read. Also, it’s the only book that I’ve read almost entirely aloud, my wife and I only pausing to let uncontrollable laughter subside before reading the passage over again.

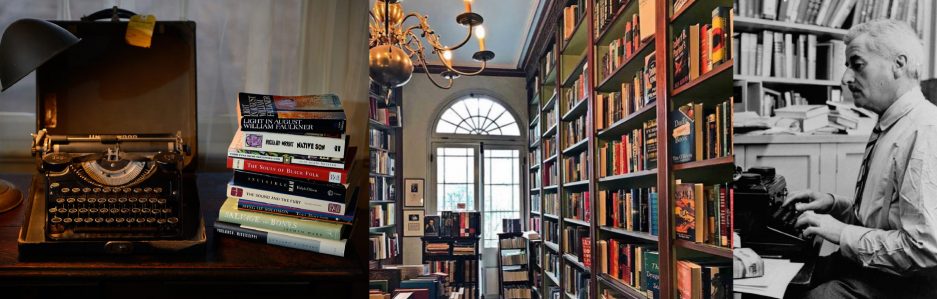

Harrison Scott Key, The World’s Largest Man: A Memoir. HarperCollins, 2015. Signed, $26.99.

Key’s humor and creative nonfiction has appeared in The Best American Travel Writing, Image, McSweeney’s, The New York Times, Outside, Reader’s Digest, and Salon. He is an editor at Oxford American where he writes a column entitled, “Big Chief Tablet”—a reference to Ignatius J. Reilly’s notes in A Confederacy of Dunces.

This first book pulls up a chair for Key at the table of Southern humor, a supper club still led by the prolific author and speaker, Roy Blount, Jr. The World’s Largest Man is a book-length love letter to his complicated and imposing, yet caring, father. It’s a collection of personal stories from childhood in rural Mississippi to adulthood in Savannah, all sewn together with threads of evolving relationships between Key and his parents and, in the later chapters, Key’s wife and daughters. However, there is nothing that I can say to enhance Key’s voice, so below is a sampling of what he brings to the table.

Key joined us in October for the 2015 Words & Music conference and signed a case of his books. Come buy one, and laugh as you read it aloud to your family over the holidays.

The first chapter begins with a context for storytelling:

They say the South is full of storytellers, but I am unconvinced. It seems more accurate to say that it is full of people who are very, very tired. At least this was my childhood experience is Mississippi, where there was very little to do but shoot things or get them pregnant. After a full day of killing and fornicating, it was only natural that everyone grew weary. So we sat around. Some would sit and nap, others would sit and drink. Frequently, there was drinking and then napping. The pious would read their Bibles, while their children would find a shady spot to know one another biblically, or perhaps give birth to a child from a previous knowing. Eventually, though, all the sitting led to talking, which supposedly led to all the stories, or at least the beginnings of stories.

In my family, we were unable to finish any. Until now.

His answer to the question, “What’s Mississippi really like?”

I can tell what they really want to ask is, What was it like to grow up around crazy people who believe that whatever can’t be shot should be baptized? But they are afraid to ask, because they are not yet sure if I am one of those people.

I am.

Kind of.

Not really.

Sometimes.

I do believe in the power of Jesus and rifles, but to keep things interesting, I also believe in the power of NPR and the scientific method. It is not easy explaining all this to educated people at cocktail parties, so instead I tell them that it was basically just like Faulkner described it, meaning that my state is too impoverished to afford punctuation, that I have seen children go without a comma for years, that I’ve seen some families save their whole lives for a semicolon.

While deer hunting with his brother, Bird:

I did what my brother said and climbed down, because while he may have lacked the ability to conjugate verbs, he would’ve known how to kill those verbs if they had been running through the forest. He was sixteen now, and he’d already killed his first, and his second, and third. Actually there was no telling how many he he’d killed. He obeyed so few hunting laws, largely as a result of his believing that he had Native American blood, which he believed absolved him from all state and federal hunting and drug statutes.

“Cherokee didn’t need no fucking hunting license,” he’d say.

What was the Trail of Tears like, I wanted to ask. Had that been hard, watching all his people die of the measles? But also, I wanted to believe. It was a story our grandmother had told us about being descended from a Cherokee chieftain, a version of the same fairy tale told to most poor whites and blacks across the South, a way of making us feel better about genocide and gambling. I’d heard that such blood could earn me a college scholarship, which I believed was my passage out of this alien land, while Bird used this story to explain his preternatural desire to learn things about animals by smelling their feces.”

As for hunting, Key prefers the grocery store:

Borden’s was our ice cream, and it came in a bucket the size of an above ground pool. How could hunting deer ever compare to hunting vanilla ice cream, which is generally docile and will let you pour syrup on it without running away?

His father’s beliefs:

My father believed a lot of crazy things: that men with earrings were queer, that the pope got to pick the Notre Dame football coach, that we couldn’t possibly have made all those expensive calls on the telephone bill. He would sit in his recliner and review the bill like some Old Testament scholar with a gift for high blood pressure….

Pop especially hated the Boy Scouts….

His only real belief about urban design was that houses should be far enough apart to let a man stand in his own front yard and relieve himself in relative privacy….

In my father’s house, having indoor pets was always a sign of moral decay, assumed to be clear evidence of mental illness and possibly drug addiction. If you wanted to get an animal into his house, you had to tell my father that you intended to eat it.

About learning to be a husband and a father:

If there is anything I learned out in the country, it was that the things that can kill you make you alive, and that you are never more alive than when you are getting beaten by your father because your mother thought you were dead.

And while to the casual observer I may not have turned out much like my father, I came to see in the first years of my marriage that I have proudly carried on this tradition of scoffing at women who are concerned for my safety, as I did with the woman I would marry….

Once we were married, she became even more like my mother, which I made sure not to tell her….

What I didn’t say was, I had very important reasons for throwing my child into the ceiling fan, and those reasons were that I wanted to see what would happen. This was my responsibility, as a man, to endanger the people I love in the service of knowledge that seems important at the time.

She asked me to stop it and all sorts of other silly things, such as to not let the baby stand on the counter and to keep the fireworks away from their faces and to lock the doors.

Lock the doors! Ridiculous!

-Alex B. Johnson, Faulkner House Books