Ever since reading Saul Bellow’s Henderson the Rain King, I’ve been an avid fan and collector of his work; I’ve read all of his books, some more than once. (Wasn’t it Somerset Maugham who said, “You truly read a book only the second time”?)

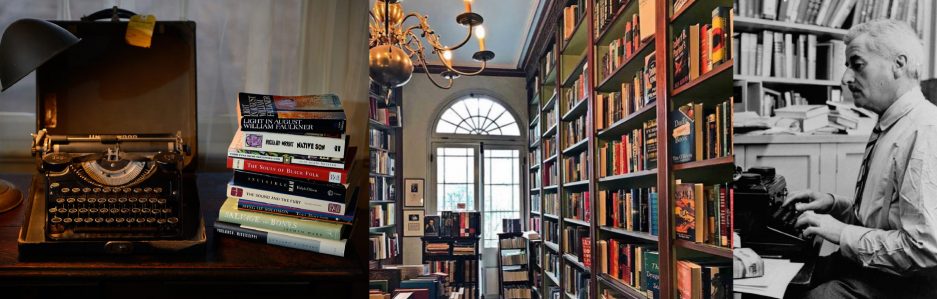

For two years after opening Faulkner House Books, we periodically published a newsletter. In one I wrote a retrospective review of Henderson and sent a copy of it to Saul Bellow with a letter thanking him for all the pleasure his writing had given me for years. Now, with the bookstore, I looked forward to sharing my pleasure with my customers. A few months later, I received his reply. Both follow.

My Review of Henderson

My ardent admiration for Saul Bellow’s Henderson the Rain King, a novel I have read often, is also a consciously expressed admission. I’m partial to Don Quixote tales where usually an aging idealist dissatisfied with things as they are seeks to change the world into something more noble. Alas, such a hero must ultimately confront reality and be either defeated or transformed and returned safely to the community of man.

And so, millionaire pig-farmer Eugene Henderson, like Don Quixote in his mid-fifties, tired of the chaos in his life, “mad as a horsefly on a window pane,” goes to Africa to quell the voice within him that repeats, “I want, I want, I want.” He also hopes to exchange what “civilization” has taught him for the more fundamental truths, he believes, primitive people still possess.

With his companion, the native Romilayu, he visits two tribes, the Arnewi and the Wariri. Both visits end disastrously. He blows up the Arnewi’s cistern while trying to rid it of an infestation of frogs. With the Wariri, he is unwittingly maneuvered into becoming the Rain King and the successor to Dahfu, their king. Dahfu is a former medical student forced to return home when his father died. He is out of favor with his elders for keeping a pet lioness in violation of tribal tradition. He befriends Henderson and insists that he can find “noble possibilities” by imitating the lioness, the way she walks and how she roars. Not long after Henderson becomes the Rain King, Dahfu is killed by another lion, perhaps not accidentally, on an obligatory hunt. Henderson succeeds to the Wariri throne, is imprisoned, but escapes and returns to the United States.

Since Henderson always believed that truth comes in blows, he is, by Dahfu’s death, redeemed, “called from non-existence into existence.” He has been moved, in his own words, “from states that I myself make into states that are of themselves. Like if I stopped making such a noise all the time, I might hear something nice. I might hear a bird.”

Henderson the Rain King was published in 1959, 18 years before Saul Bellow won the Nobel Prize for literature. It is truly a masterpiece, delightfully humorous and invariably intelligent. It is a novel for poets; a worthy scion of Cervantes’ Don Quixote.

January 26, 1993

Saul Bellow’s Response

Dear Mr. De Salvo,

It makes me happy to hear from members of what I consider to be an elite of readers, namely those who admire Henderson the Rain King. I am especially fond of, “I might hear a bird.” So, it’s turnabout and fair play. I write a book, you send me a kind note.

With Best Wishes,

Saul Bellow

You should infer from Bellow’s letter that Henderson was a favorite of his, even though he was critiqued for moving away from his urban Jewish theme; also for being uninformed about Africa and for using a minstrel-style Southern dialect for the natives. The novel is so thoughtful, so intelligent and funny, and Henderson the character is such a marvelous creation, that the criticisms pale.

Good reading to you.

Joe DeSalvo